Dazed Digital

[ link ]

Tracey Moberly

Haiti Ghetto Biennale

One Month before the Earthquake

28 January 2010

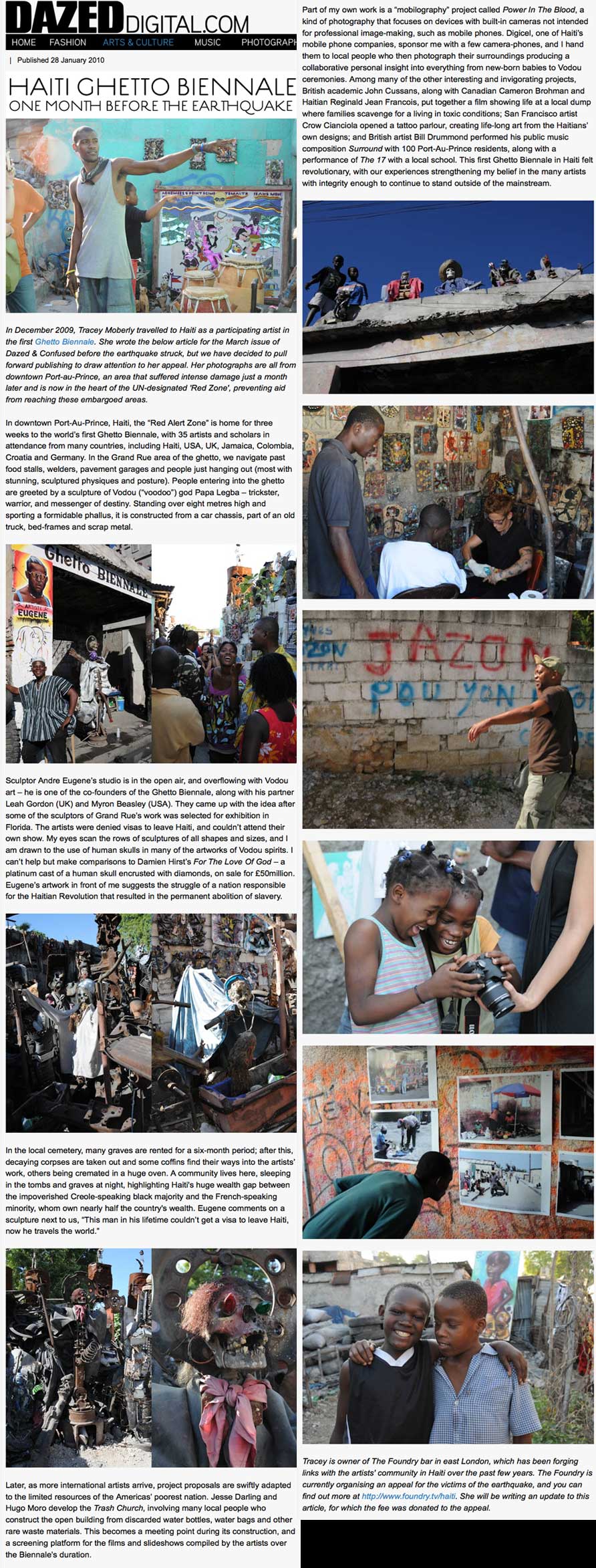

In December 2009, Tracey Moberly travelled to Haiti as a participating artist in the first Ghetto Biennale. She wrote the below article for the March issue of Dazed & Confused before the earthquake struck, but we have decided to pull forward publishing to draw attention to her appeal. Her photographs are all from downtown Port-au-Prince, an area that suffered intense damage just a month later and is now in the heart of the UN-designated 'Red Zone', preventing aid from reaching these embargoed areas.

In downtown Port-Au-Prince, Haiti, the ìRed Alert Zoneî is home for three weeks to the worldís first Ghetto Biennale, with 35 artists and scholars in attendance from many countries, including Haiti, USA, UK, Jamaica, Colombia, Croatia and Germany. In the Grand Rue area of the ghetto, we navigate past food stalls, welders, pavement garages and people just hanging out (most with stunning, sculptured physiques and posture). People entering into the ghetto are greeted by a sculpture of Vodou (ìvoodooî) god Papa Legba ñ trickster, warrior, and messenger of destiny. Standing over eight metres high and sporting a formidable phallus, it is constructed from a car chassis, part of an old truck, bed-frames and scrap metal.

Sculptor Andre Eugeneís studio is in the open air, and overflowing with Vodou art ñ he is one of the co-founders of the Ghetto Biennale, along with his partner Leah Gordon (UK) and Myron Beasley (USA). They came up with the idea after some of the sculptors of Grand Rueís work was selected for exhibition in Florida. The artists were denied visas to leave Haiti, and couldnít attend their own show. My eyes scan the rows of sculptures of all shapes and sizes, and I am drawn to the use of human skulls in many of the artworks of Vodou spirits. I canít help but make comparisons to Damien Hirstís For The Love Of God ñ a platinum cast of a human skull encrusted with diamonds, on sale for £50million. Eugeneís artwork in front of me suggests the struggle of a nation responsible for the Haitian Revolution that resulted in the permanent abolition of slavery.

In the local cemetery, many graves are rented for a six-month period; after this, decaying corpses are taken out and some coffins find their ways into the artistsí work, others being cremated in a huge oven. A community lives here, sleeping in the tombs and graves at night, highlighting Haiti's huge wealth gap between the impoverished Creole-speaking black majority and the French-speaking minority, whom own nearly half the country's wealth. Eugene comments on a sculpture next to us, ìThis man in his lifetime couldnít get a visa to leave Haiti, now he travels the world.î

Later, as more international artists arrive, project proposals are swiftly adapted to the limited resources of the Americasí poorest nation. Jesse Darling and Hugo Moro develop the Trash Church, involving many local people who construct the open building from discarded water bottles, water bags and other rare waste materials. This becomes a meeting point during its construction, and a screening platform for the films and slideshows compiled by the artists over the Biennaleís duration.

Part of my own work is a ìmobilographyî project called Power In The Blood, a kind of photography that focuses on devices with built-in cameras not intended for professional image-making, such as mobile phones. Digicel, one of Haitiís mobile phone companies, sponsor me with a few camera-phones, and I hand them to local people who then photograph their surroundings producing a collaborative personal insight into everything from new-born babies to Vodou ceremonies. Among many of the other interesting and invigorating projects, British academic John Cussans, along with Canadian Cameron Brohman and Haitian Reginald Jean Francois, put together a film showing life at a local dump where families scavenge for a living in toxic conditions; San Francisco artist Crow Cianciola opened a tattoo parlour, creating life-long art from the Haitiansí own designs; and British artist Bill Drummond performed his public music composition Surround with 100 Port-Au-Prince residents, along with a performance of The 17 with a local school. This first Ghetto Biennale in Haiti felt revolutionary, with our experiences strengthening my belief in the many artists with integrity enough to continue to stand outside of the mainstream.

Tracey is owner of The Foundry bar in east London, which has been forging links with the artists' community in Haiti over the past few years. The Foundry is currently organising an appeal for the victims of the earthquake, and you can find out more at http://www.foundry.tv/haiti. She will be writing an update to this article, for which the fee was donated to the appeal.

Link

http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/6425/1/haiti-ghetto-biennale