[press - foundry]

[<<<] [>>>] click on image to enlarge

© tracey moberly 20100212.snob.jpg

SNOB.ru

[ link ]

Tracey Moberly

Found and lost

The plight of London's alternative culture: a case study

24/02/10

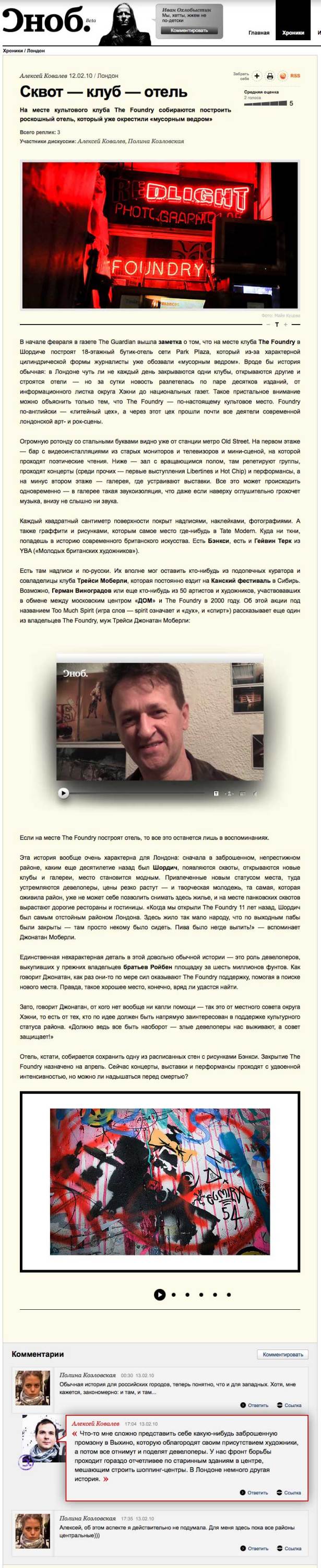

The Foundry is probably the biggest of London's alternative venues. Its massive rotunda with enormous steel letters on the facade sits in the very centre of Shoreditch, a five-minute walk from Old Street station. Inside on the ground floor is a bar, its walls decorared with murals and photographs. Two floors down are a concert hall and a gallery space. The former hosted innumerable first gigs of today's national favourites like The Hot Chip and enfant terribles such as The Libertines. The latter's frontman Pete Doherty, once a pink-cheeked talent boy and not the drug wreck of late, held his poetry evenings on the mini-stage upstairs.

All events at The Foundry - poetry readings, ear-wrenchingly loud gigs and gallery openings - are free of charge and quite often happen at the same time. The Foundry occupies the former Barclays building, its walls being so thick that they can probably withstand a direct missile hit, let alone a few extra decibels. Every single inch of the venue's inner is covered in graffiti, stickers and murals. Every square foot deserves a place at Tate Modern - you can randomly poke at the wall with your finger and hit Banksy or Gaving Turk of the Young British Artists (YBA).

What doesn't have an immediate artistic value is covered in scribbles, humorous and not always quite decent. A keen eye can locate, for example, a sly pun in Russian ridiculing the British stiff upper lip. It could have been left by one of the fifty Russian performance artists and musicians brought to The Foundry by Tracey Moberly, one of the venue's owners, as part of a cultural exchange with DOM, a cultural space in Moscow, Russia.

The ordeal with DOM was quite sympthomatic of the situation in the late nineties. Jonathan Moberly, Tracey's husband and the second owner, explains: "I met DOM's curators during my trip to Moscow and we came up with this idea to swap venues. We put fifty British artists on a coach and went to Moscow and they did the same thing. The whole thing was funded by the British Council, which is quite interesting, because they normally give money to British people to take propaganda abroad. But we said 'No, that won't work, this is a cultural exchange, it must be both ways'. So they went 'OK, here's a travel budget, we won't ask what you do with it'. This was fantastic!"

But the nineties, the glorious time of infinite possibilities and bottomless budgets, came to an end. The Foundry now faces the same unfortunate fate as several other legendary venues such as The Astoria or Manchester's Hacienda. The story is depressingly familiar: first some young artsy types move into a run-down area attracted by the abundance of cheap (or just abandoned and thus free altogether) housing for their workshops and galleries. The area then flourishes, new fashionable bars and restaurants sprout like mushrooms after a warm summer rain. Property value rockets, and then there's a dot blinking on an opportunistic real estate dealer's radar. The spin begins, and in a few months a neighbourhood so poor that even stray dogs would avoid it becomes "a fashion centre" with prices starting at #300,000 for a small studio flat. Councils sell planning permissions to the highest bidder, while the artists, i.e. the very people who gave the area a new life, can no longer afford the rent and have to move elsewhere. The cycle begings anew a few miles further from London's centre, in another not-so-prime location.

Shoreditch is a textbook example of that cycle. "When we started The Foundry eleven years ago, Shoreditch was so empty that the pubs were closed on weekends. There wasn't simply anyone to sit in them. You coulnd't get a beer anywhere! And around the corner is Hoxton, the poorest area in England. It's so poor that it receives EU funding. But they don't mention it in real estate ads".

The Moberlys' cult venue now must give place to a 18-storey boutique hotel already dubbed 'flip-top bin' by the public for its distinctive tubular shape. The plot on which The Foundry sits was sold by its owners, metal moguls Reuben brothers, to an international hotel chain Park Plaza earlier this year. The only unusual detail in this sad but otherwise quite typical story are the reversed roles of the developers and Hackney council which granted the planning permission despite all the objections from The Foundry's owners and a media protest campaign that ensued. "It's supposed to be the other way round: the developers are the bad guys and the council protects us from them!", says Jonathan. The hotel owners have expressed the wish to preserve an iconic Banksy mural on one of the walls and are generally quite supportive, he adds. Hackney council, on the other hand, has consistently refused to consider the venue's special cultural status referring to it in the documents as simply a "bar".

If a miracle does not happen, The Foundry is set to close its doors for ever in late April. The only real alternative is relocation - if the Moberlys find an appropriate venue, that is. Jonathan nods his head sceptically. "What they can offer us is on the borough's margins, somewhere in Hackney Wick. It's quite a long way from here". Meanwhile inside the place they are not losing a single second of the precious time that is left until the premises are set to be vacated. There is a gig, an exhibition or a performance every single day. The Foundry does its best to be remembered.